Section 60i of the Family Law Act is one of the most important provisions Australian parents need to understand. It shapes how courts make decisions about parenting arrangements, custody, and your child’s welfare.

At Jameson Law, we’ve helped countless families navigate this section and its real-world implications. This guide breaks down what Section 60i means for you and your family.

What Section 60I Actually Requires

The Mandatory FDR Requirement

Section 60I of the Family Law Act 1975 sits at the centre of parenting disputes in Australia. It mandates that before you apply to court for parenting orders, you must attempt Family Dispute Resolution (FDR) with an accredited practitioner. This is not optional or advisory-it is a legal requirement that the court takes seriously. The legislation exists because Australian family law prioritises resolving disputes outside the courtroom whenever possible. When you skip FDR or fail to genuinely engage with it, your application gets rejected at the filing stage, costing you time and money.

Section 60I forces a pause before litigation. It gives parents a structured opportunity to reach agreement without the adversarial nature of court proceedings. If you reach an agreement during FDR, you can formalise it through a parenting plan or consent orders. If FDR fails, you obtain a Section 60I certificate proving you made a genuine effort, and only then can you proceed to court.

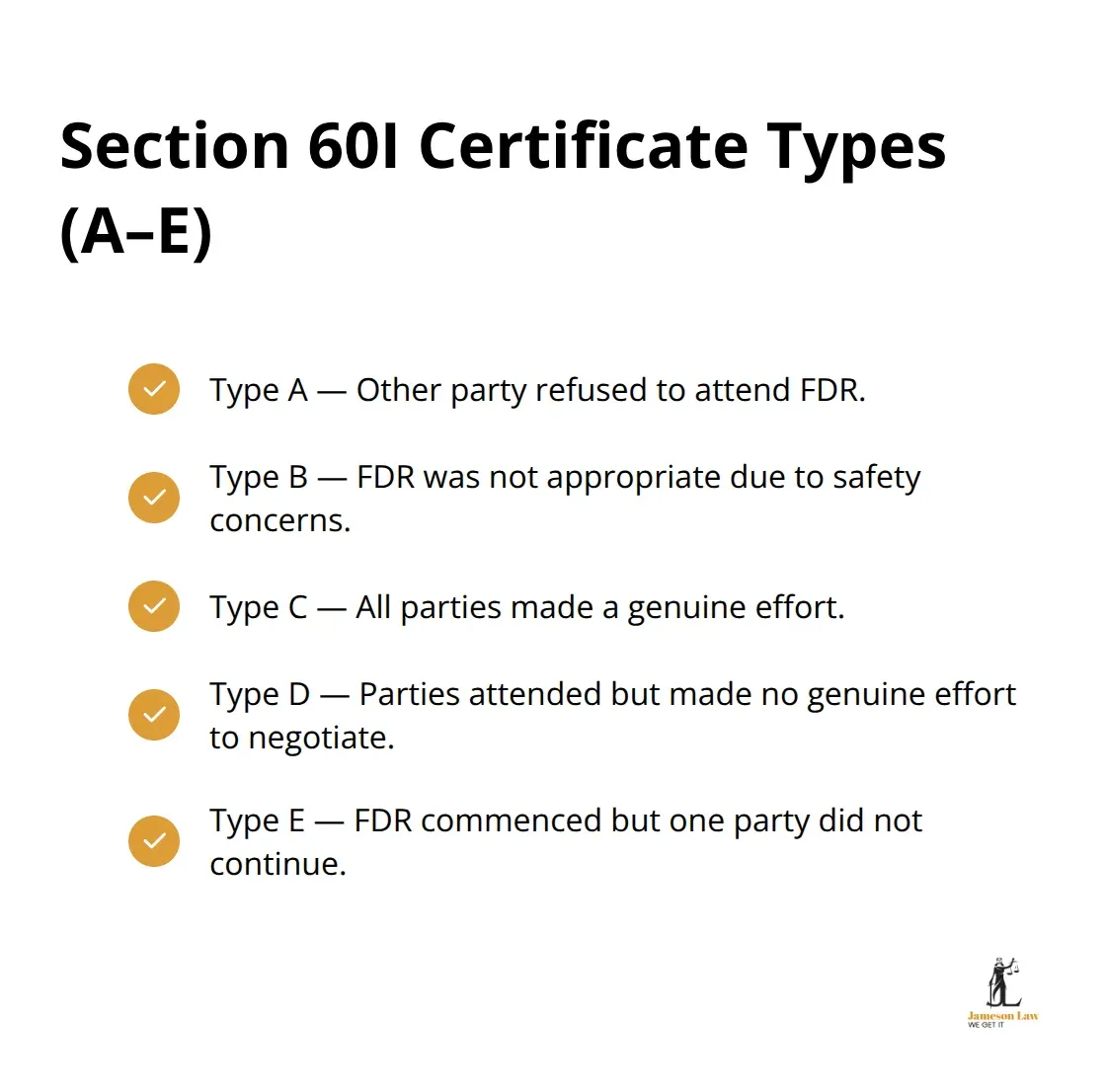

Understanding the Five Certificate Types

The certificate itself comes in five types, each reflecting what happened during your FDR process. Type A applies when the other party refused to attend. Type B applies when FDR was not appropriate due to safety concerns. Type C indicates that genuine effort occurred from all parties. Type D shows that parties attended but made no genuine effort to negotiate. Type E applies when FDR started but one party didn’t continue.

Courts use these certificates to assess your conduct and may order additional FDR or impose cost orders against parties who didn’t engage properly.

The last FDR session must have occurred within 12 months of issuing the certificate-this 12-month window is absolute. Missing this deadline means you cannot use that certificate and must start the FDR process again.

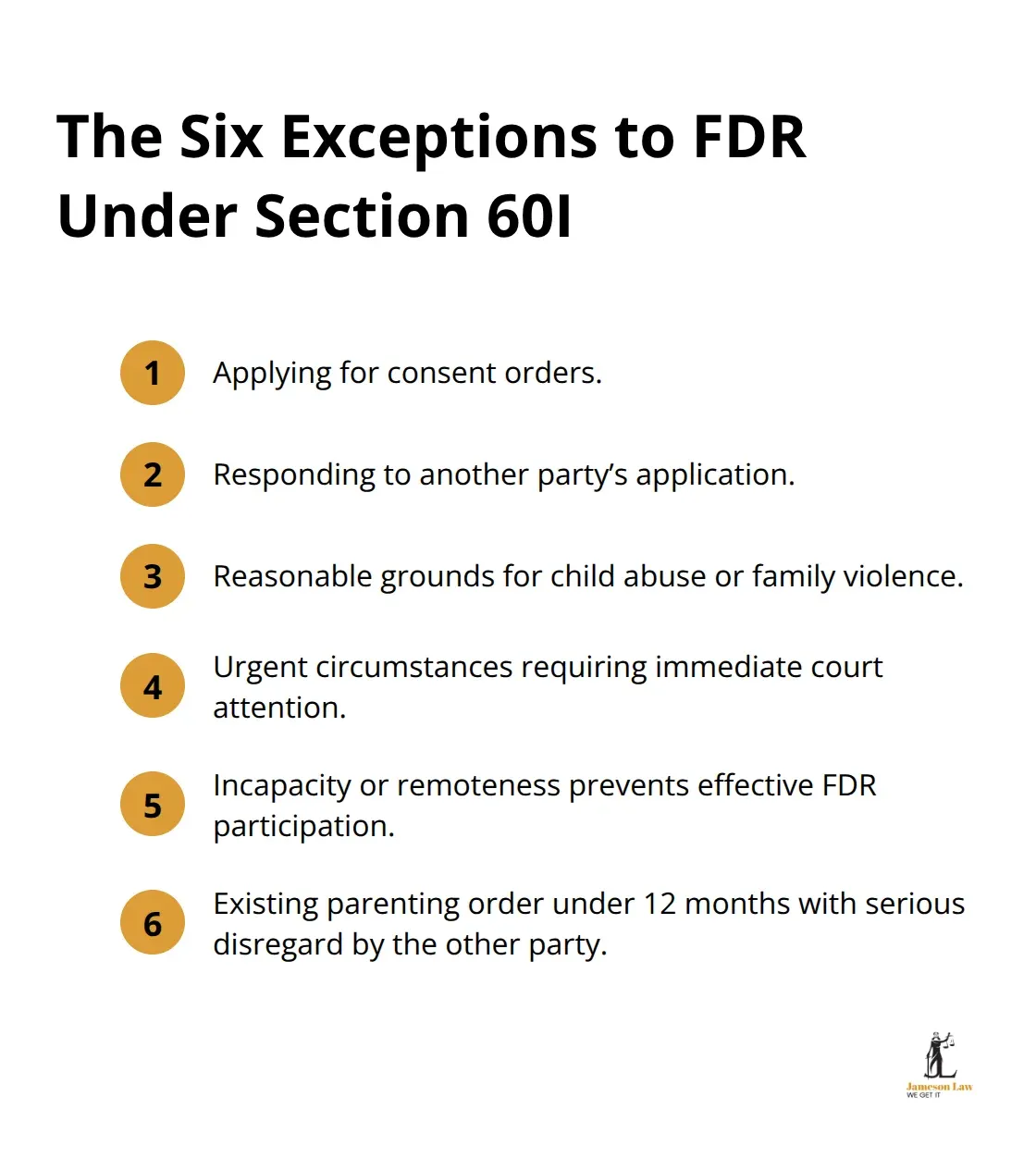

The Six Exceptions to FDR

Six exceptions exist where you can bypass FDR entirely. You don’t need a certificate if you apply for consent orders, respond to another party’s application, have reasonable grounds to believe child abuse or family violence has occurred, face an urgent situation, cannot participate effectively in FDR due to incapacity or remoteness, or the existing parenting order is less than 12 months old with serious disregard by the other party. However, courts scrutinise these exemptions closely. The burden sits with you to prove the exception applies.

Accreditation and Cost Considerations

FDR practitioners must be accredited by the Commonwealth Attorney-General’s Department and hold a valid registration number-practitioners with suspended or cancelled accreditation cannot issue certificates. Government-subsidised FDR through Family Relationship Centres costs nothing for the first hour per couple; sessions beyond that cost $30 per hour per couple if your gross annual income exceeds $50,000. Those earning less or receiving certain benefits pay nothing. Court-based FDR through a judicial registrar is completely free.

This accessibility matters because genuine engagement with FDR significantly improves outcomes. Families reaching agreement at FDR experience less ongoing conflict and better compliance with arrangements than those forced into court. Most parents don’t realise that attempting FDR in good faith, even if unsuccessful, actually strengthens your case later. Courts view genuine effort positively and may order cost penalties against parties who attend FDR but refuse to negotiate reasonably.

How Section 60I Differs from Other Provisions

The distinction between Section 60I and other family law provisions is critical. Section 60I is procedural-it governs how you access the court system. Other provisions (such as those dealing with parental responsibility or the best interests of the child) are substantive-they determine what the court actually decides once you’re in the system. You cannot proceed without satisfying Section 60I first. Understanding this procedural requirement sets the foundation for what courts actually examine when they assess your parenting arrangements and your child’s welfare.

What Courts Actually Look At in Parenting Disputes

The Best Interests Standard in Action

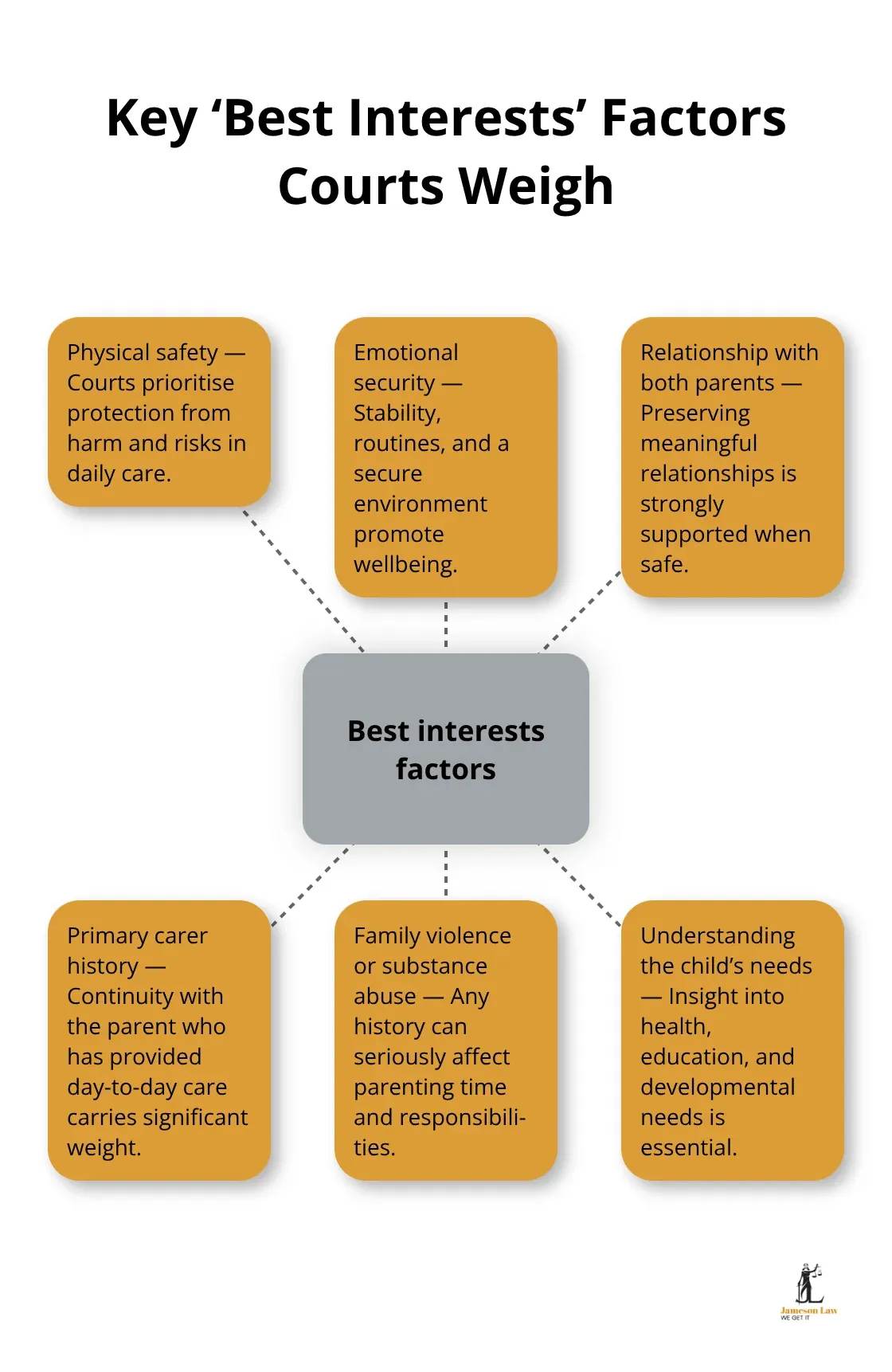

When courts assess parenting arrangements under Section 60I, they examine concrete facts about your child’s life, your capacity to parent, and the other party’s conduct during FDR. The best interests of the child standard sits at the centre of every decision, but this isn’t a blank slate that courts fill in however they wish. Australian courts have applied this standard consistently for decades, and specific factors appear repeatedly in judgements. Your child’s physical safety, emotional security, and relationship with both parents matter most. Courts assess which parent has been the primary carer historically, whether either parent has engaged in family violence or substance abuse, and how well each parent understands the child’s needs. If you’ve been the primary carer for years, courts recognise this as a significant factor.

If the other party has breached previous orders, courts take that seriously when deciding whether to grant new arrangements.

The Federal Circuit and Family Court of Australia consistently prioritises stability and continuity in a child’s life, which means disrupting existing arrangements requires substantial justification. Courts examine parental responsibility and decision-making capacity beyond who picks up the child from school. This involves who makes medical decisions, educational choices, and religious upbringing decisions. Parents with shared parental responsibility must consult each other on major matters, and courts assess whether you’ve demonstrated this collaborative approach. If you’ve made major decisions without consulting the other parent, courts view this negatively even if your decision was reasonable.

Parental Conduct During FDR and Previous Proceedings

Courts heavily weigh how you’ve conducted yourself during FDR and any previous proceedings. Type C certificates showing genuine effort from all parties significantly improve your credibility. Type D certificates, indicating you attended but refused to negotiate, create a negative impression that’s difficult to overcome. During FDR, genuine engagement with the other party on major decisions strengthens your position. Practitioners report that parents who arrive prepared with specific proposals about schooling, healthcare, and holiday arrangements reach agreement more often than those who argue only about general principles.

One major factor courts consider is your willingness to facilitate the child’s relationship with the other parent. If you’ve prevented contact, made negative comments about the other parent to the child, or failed to return the child on time, expect courts to view you unfavourably. Conversely, demonstrating that you’ve consistently supported the child’s relationship with the other parent, even when that parent hasn’t reciprocated, positions you as a child-focused parent rather than a conflict-driven one.

Financial Capacity and Child Preferences

Courts examine financial capacity too. Which parent can afford better housing, education, and healthcare? However, this doesn’t mean the wealthier parent automatically wins. Courts balance financial factors against other considerations like emotional bonds and existing care arrangements. A parent with modest income who has been the primary carer typically has stronger standing than a high-income parent who has had minimal involvement.

Courts assess the child’s own preferences, though weight given to these preferences depends on the child’s age and maturity. Children under eight rarely influence outcomes significantly. Teenagers, however, substantially impact decisions, especially if they’ve clearly expressed a preference and can articulate reasons beyond simple preference for the more permissive parent. As your child’s circumstances evolve and their voice becomes stronger, courts increasingly look to what they actually want from their parenting arrangements-which means understanding how courts weigh these preferences becomes essential when you’re preparing for the next stage of your case.

When Section 60I Applies to Your Parenting Situation

Understanding When Section 60I Kicks In

Most parents think Section 60I only matters when they head to court, but this misses the real picture. Section 60I affects parenting orders from the moment you decide to formalise any arrangement through the courts, whether you seek initial orders, relocate interstate, or modify existing arrangements. The Federal Circuit and Family Court of Australia won’t accept your application without satisfying Section 60I first, which means you need an accredited FDR practitioner’s certificate before filing. If you apply for consent orders because you and the other parent have already agreed on arrangements, you still technically need a certificate, though courts treat consent applications more leniently.

The practical reality is that you should engage with FDR early, not as an afterthought when you prepare court documents. Families who approach FDR strategically, with specific proposals about schooling arrangements, holiday schedules, and living expenses, reach agreement far more often than those who treat FDR as a box-ticking exercise.

Relocation and Interstate Moves

When you relocate interstate or want to modify existing orders, Section 60I applies again unless you meet one of the six exceptions. If you relocate with a child and the other parent objects, courts require fresh FDR before hearing your application. This delay frustrates many parents, but it serves a purpose: FDR often surfaces compromises that court litigation would never reach. A parent relocating for work might agree to extended school holidays with the other parent, or agree to fund flights for regular contact, rather than fighting in court over whether relocation should happen at all.

Courts heavily favour parents who demonstrate genuine flexibility during FDR, even when they don’t reach full agreement. Approaching FDR with detailed proposals about how the child’s needs will be met under new circumstances strengthens your position significantly. Courts assess whether you’ve thought through practical details like school transitions, maintaining the child’s relationship with the other parent, and financial arrangements.

Modifying Existing Orders

When you modify existing orders, the 12-month rule becomes critical. Your previous Section 60I certificate expires 12 months after your last FDR session, so if you seek modifications beyond that timeframe, you must complete FDR again. Many parents don’t realise this and attempt to file modifications with expired certificates, causing their applications to be rejected. The Commonwealth Attorney-General’s Department maintains the register of accredited FDR practitioners, and you can verify a practitioner’s registration number before engaging them, which matters because only currently accredited practitioners can issue valid certificates.

Parents who arrive at FDR with these specifics mapped out typically achieve better outcomes than those who rely on general arguments about what’s best for the child.

Non-Cooperation and Type D Certificates

If the other parent refuses to genuinely negotiate during FDR, you’ll receive a Type D certificate, which courts recognise as evidence of non-cooperation. This doesn’t prevent you from proceeding to court, but it does mean you’ll need to justify why court intervention is necessary when the other party wouldn’t engage in good faith negotiation. Courts view Type D certificates as indicators that one party has blocked resolution, which can influence how judges assess costs and the credibility of each parent’s position in subsequent proceedings.

Final Thoughts

Section 60I of the Family Law Act fundamentally shapes how Australian parents access the court system for parenting disputes. Understanding this requirement matters if you navigate family law matters. The mandatory Family Dispute Resolution process exists because courts recognise that agreements reached outside litigation hold better over time and reduce ongoing conflict between parents.

The practical reality is straightforward: before filing any parenting orders application, you need an accredited FDR practitioner’s certificate unless you qualify for one of the six exceptions. Arriving at FDR with specific proposals about schooling, healthcare decisions, and holiday arrangements significantly improves your chances of reaching agreement. Courts assess not just what you propose but how you conduct yourself throughout the process, and parents who demonstrate flexibility position themselves far more favourably than those who treat FDR as an obstacle.

If you face parenting disputes, relocation questions, or modifications to existing orders, contact Jameson Law to discuss your family law matter with experienced practitioners who understand how courts apply Section 60I to your circumstances.