Binding financial agreements under Section 90B of the Family Law Act offer couples a way to settle property and financial matters outside court. At Jameson Law, we’ve seen how these agreements can provide certainty and control when structured correctly.

Getting Section 90B right matters because mistakes can make an agreement unenforceable. This guide walks you through what you need to know to protect your interests.

What Section 90B Actually Protects

Section 90B lets couples entering marriage formalise their financial arrangements before saying their vows. This is a binding financial agreement made under the Family Law Act 1975 that sits outside the court system entirely. When you sign a valid 90B agreement, neither party can later bring a claim in the Family Court or Federal Circuit Court for property adjustment. That’s the real power of this mechanism-it removes uncertainty and prevents one spouse from challenging the arrangement years down the track. The agreement can cover how property and financial resources get divided if the marriage ends, maintenance obligations during the relationship and after divorce, and various incidental matters tied to those core issues. Courts won’t intervene once the agreement is binding, which means you control the outcome rather than leaving it to judicial discretion. This matters most when significant assets are involved, when one partner brings substantial wealth into the marriage, or when both parties want clarity about what happens to their separate property.

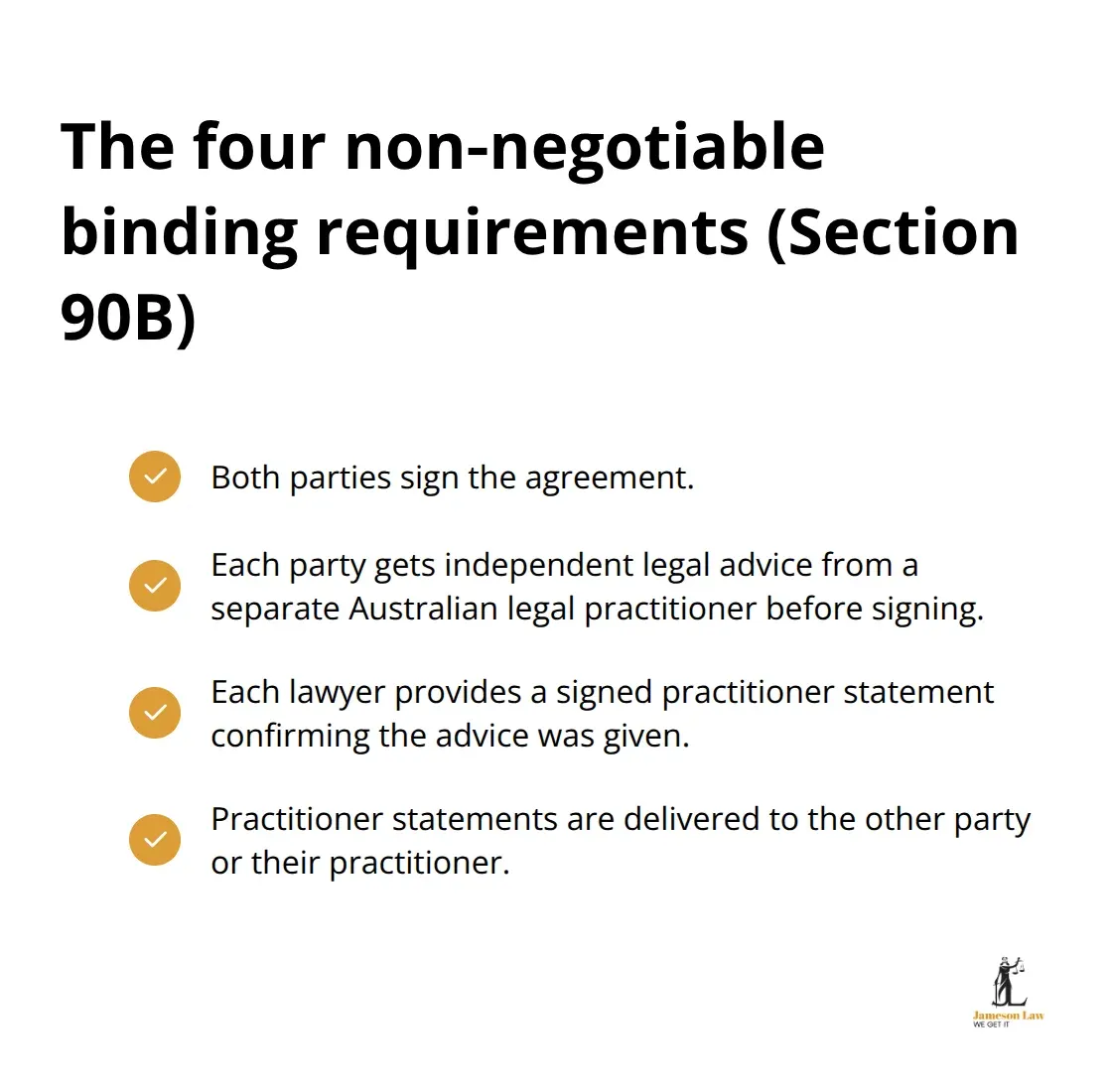

The Four Non-Negotiable Requirements

For a 90B agreement to actually bind both parties, four conditions must be met simultaneously. All parties must sign the agreement. Each party must receive independent legal advice from an Australian legal practitioner before signing-this cannot be waived and must come from separate lawyers. Each party’s lawyer must provide a signed practitioner statement confirming the advice was given.

Those practitioner statements must be given to the other party or their practitioner. This is not flexible. In Graham v Squibb, the court ruled that mutual intention to be bound matters more than exact wording, yet the four technical requirements still apply without exception. Courts have consistently held that a mere certificate of advice is insufficient; the advice must be real and substantive, explaining the effect on rights and the advantages and disadvantages of giving them up. If any of these four elements is missing or defective, the agreement fails.

Disclosure and Valuation Standards

Disputes often arise from incomplete disclosure. Full and frank disclosure of all assets, liabilities, financial resources, superannuation, trusts, expected inheritances, and business interests is mandatory. Vague or broad schedules describing quarantined property create later disputes over what was actually protected. Professional valuations for significant assets like businesses or investment properties aren’t optional-they’re essential to prove disclosure was genuine. Courts scrutinise agreements where one party withheld material information, and they will set aside an agreement if a party knowingly or recklessly makes false statements or misrepresents their circumstances.

Timing and Pressure Considerations

Presenting the agreement days before the wedding or under time pressure invites a court to find duress or undue influence and set it aside. Negotiating several months in advance removes this risk entirely. Courts have found that last-minute presentations can amount to unconscionable conduct, even when both parties obtained independent legal advice. The earlier you start these conversations, the stronger your agreement becomes.

What Happens Next

With these foundational protections in place, the actual drafting and execution process determines whether your agreement will withstand scrutiny. The next section covers the essential elements that must appear in your agreement and the documentation you need to gather before your lawyers put pen to paper.

Getting Your Agreement Right Before Signing

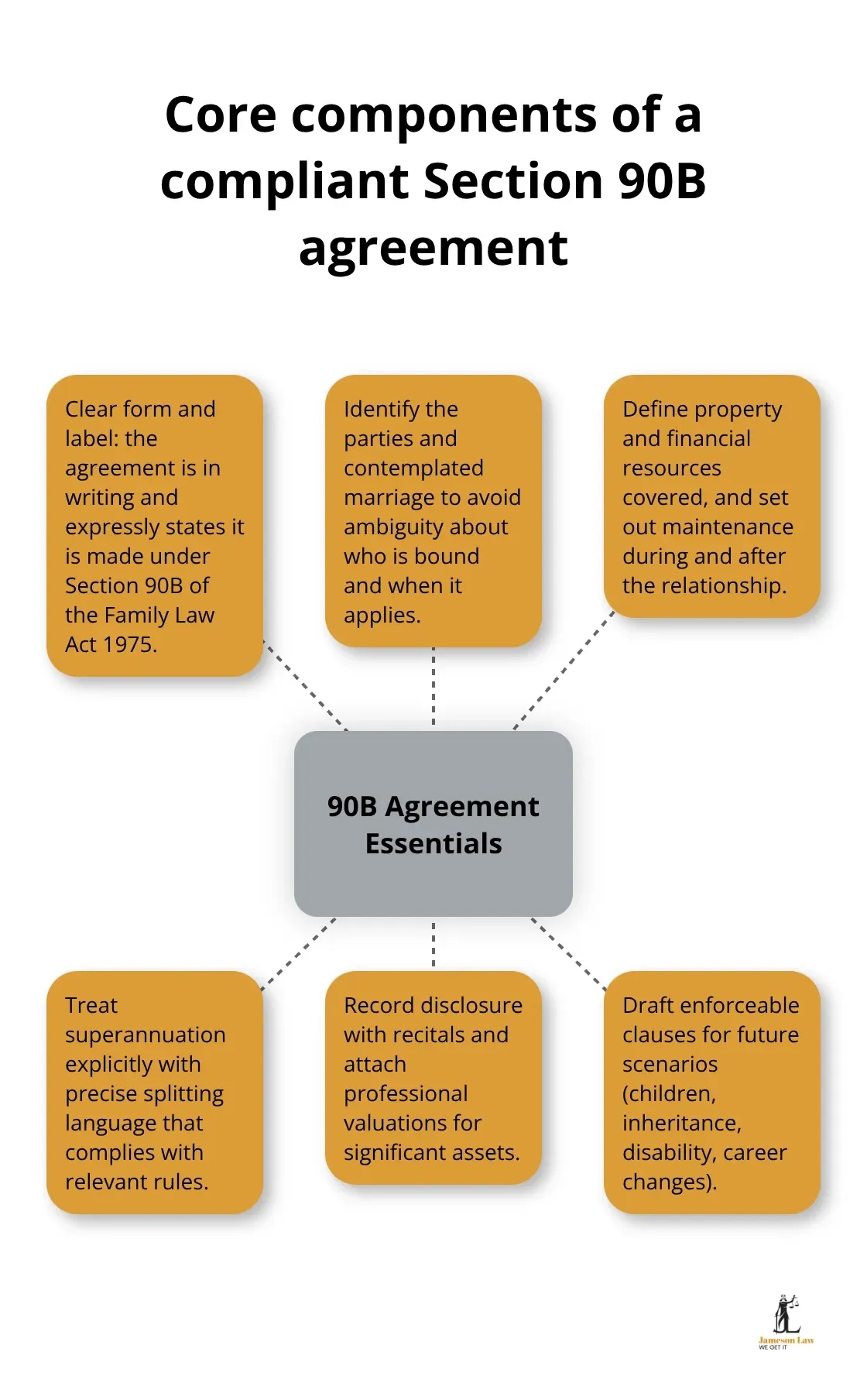

A compliant 90B agreement requires specific structural elements that courts will scrutinise if the arrangement ever faces challenge. The agreement must be in writing and expressly state it is a financial agreement made under Section 90B of the Family Law Act 1975. This isn’t bureaucratic box-ticking-courts in Graham v Squibb emphasised that clear labelling signals genuine mutual intention to be bound.

Your agreement should identify each party, describe the contemplated marriage, specify what property or financial resources are covered, detail how maintenance will be handled during and after the relationship, and address superannuation explicitly as property rather than leaving it ambiguous. Many agreements fail because drafters treat superannuation as secondary, yet splitting entitlements under superannuation splitting rules requires precise language complying with relevant splitting rules. Include clear recitals documenting what disclosure each party made, whether any disclosure was waived, and what independent legal advice each party received. Vague descriptions of quarantined assets invite later disputes-if you’re protecting a family business worth $2 million, name it specifically with its ABN, asset register details, and current valuation rather than writing something generic like other business interests. Professional valuations for significant assets aren’t optional extras; courts treat them as evidence of genuine disclosure. If the agreement addresses future scenarios (children being born, inheritance, disability, or career changes), draft these provisions with enough detail that a court can actually enforce them rather than finding them impracticable or too uncertain.

Independent Legal Advice as Your Enforceability Backbone

Independent legal advice requirements operate as the enforceability backbone, and getting this wrong destroys the entire agreement. Each party must obtain advice from a separate Australian legal practitioner before signing-no exceptions, no shared lawyers, no advice after the fact. The lawyer must explain the effect of the agreement on the party’s legal rights, the advantages and disadvantages of entering the agreement, and the disadvantages of not entering it. Courts have rejected agreements where lawyers issued generic certificates without substantive discussion of what the party was giving up. If one spouse earns $180,000 annually and the other earns $45,000, the advice must address what spousal maintenance rights are forfeited and why that’s justifiable given the income disparity. The lawyer must provide a signed practitioner statement confirming this advice was given, and that statement must reach the other party or their practitioner before signing. This creates an audit trail. Keep copies of all valuations, disclosure documents, financial statements, tax returns, superannuation statements, and the practitioner statements together with the executed agreement. Courts have set aside agreements years later because one party claimed they never received proper disclosure or advice-complete documentation protects both parties.

Timing Matters More Than You Think

Draft the agreement months before the wedding, not weeks. Presenting it two weeks before the ceremony invites findings of duress or unconscionable conduct that courts will use to invalidate the entire arrangement, regardless of whether both parties obtained legal advice. The time gap demonstrates genuine negotiation rather than pressure. Courts have found that last-minute presentations amount to unconscionable conduct, even when both parties obtained independent legal advice. The earlier you start these conversations, the stronger your agreement becomes.

Predictable Failures You Must Avoid

DIY templates from generic websites fail because they don’t account for the specific technical requirements of Section 90B or the unique circumstances of your relationship and assets. Incomplete disclosure-omitting a rental property, understating business value, or ignoring expected inheritances-gives the other party grounds to set the agreement aside under Section 90K. Misdescribing assets creates uncertainty; if the agreement refers to a property by street address but the actual legal description differs, courts may find the agreement too vague to enforce. Mixing quarantined and non-quarantined property without clear boundaries creates ambiguity about what’s protected and what’s subject to property division if the marriage ends. Failing to address superannuation specifically leaves the largest asset class unprotected and potentially subject to challenge. Signing without independent legal advice, or having one lawyer advise both parties, invalidates the agreement entirely-courts won’t overlook this procedural requirement. Not obtaining or attaching the practitioner statements means the other party can later claim they never received proper advice, and you’ll struggle to prove otherwise. Presenting the agreement under time pressure, financial duress, or family coercion gives grounds to set it aside even if technical requirements were met. Professional legal assistance at the drafting stage prevents these failures rather than trying to repair them later through costly litigation.

Once you’ve structured your agreement correctly and obtained proper independent legal advice, the real test comes when circumstances change or one party challenges the arrangement. The next section examines how courts assess the validity of agreements and what grounds exist for setting them aside.

When Courts Reject a Section 90B Agreement

How Courts Assess Validity

Courts assess the validity of Section 90B agreements against strict technical and substantive criteria, and they set aside an agreement if any element fails scrutiny. The four binding requirements form the foundation, but courts also examine whether the agreement meets the requirements under Section 90G. Each party must have received independent legal advice that was real and meaningful, not merely a generic certificate of advice. In Kaimal & Kaimal, the court rejected an agreement where the lawyer issued a practitioner statement without substantively discussing what rights the party was forfeiting. This matters because courts treat independent legal advice as the enforceability backbone. If one spouse earned significantly more than the other or brought substantial assets into the marriage, the advice must specifically address what maintenance rights or property entitlements were being surrendered and why that outcome was justifiable.

Disclosure Failures That Trigger Challenges

Courts scrutinise whether disclosure was full and frank. If a party omitted a rental property, understated business value, or failed to disclose expected inheritances, the other party has grounds to challenge the agreement under Section 90K. In Daily & Daily, the court found that vague descriptions of quarantined property created uncertainty about what was actually protected, and this ambiguity rendered parts of the agreement unenforceable. Incomplete or inaccurate disclosure remains one of the most common reasons courts set aside agreements that otherwise met technical requirements.

Timing and Pressure as Grounds for Challenge

The timing of when the agreement was presented matters significantly. If one spouse presented the agreement days before the wedding, courts will often find duress or unconscionable conduct and set the agreement aside entirely, even if both parties obtained legal advice. The earlier the agreement is negotiated and signed before the marriage, the stronger your enforceability position becomes. Courts have found that last-minute presentations amount to unconscionable conduct, regardless of whether both parties obtained independent legal advice.

Specific Grounds for Setting Aside Under Section 90K

A party can apply to set aside the agreement if they knowingly or recklessly made false statements or misrepresented their circumstances during disclosure, if the agreement was entered into to defeat creditors’ claims, if it is incomplete or impracticable to carry out, or if unconscionable conduct, undue influence, or duress affected the agreement. Courts in Thorne v Kennedy established a practical six-point framework for assessing undue influence that examines whether special disadvantage existed, whether the stronger party unconscientiously took advantage of that disadvantage, and whether the weaker party’s consent was genuine. Understanding these grounds helps you either defend your agreement or identify weaknesses if you need to challenge one.

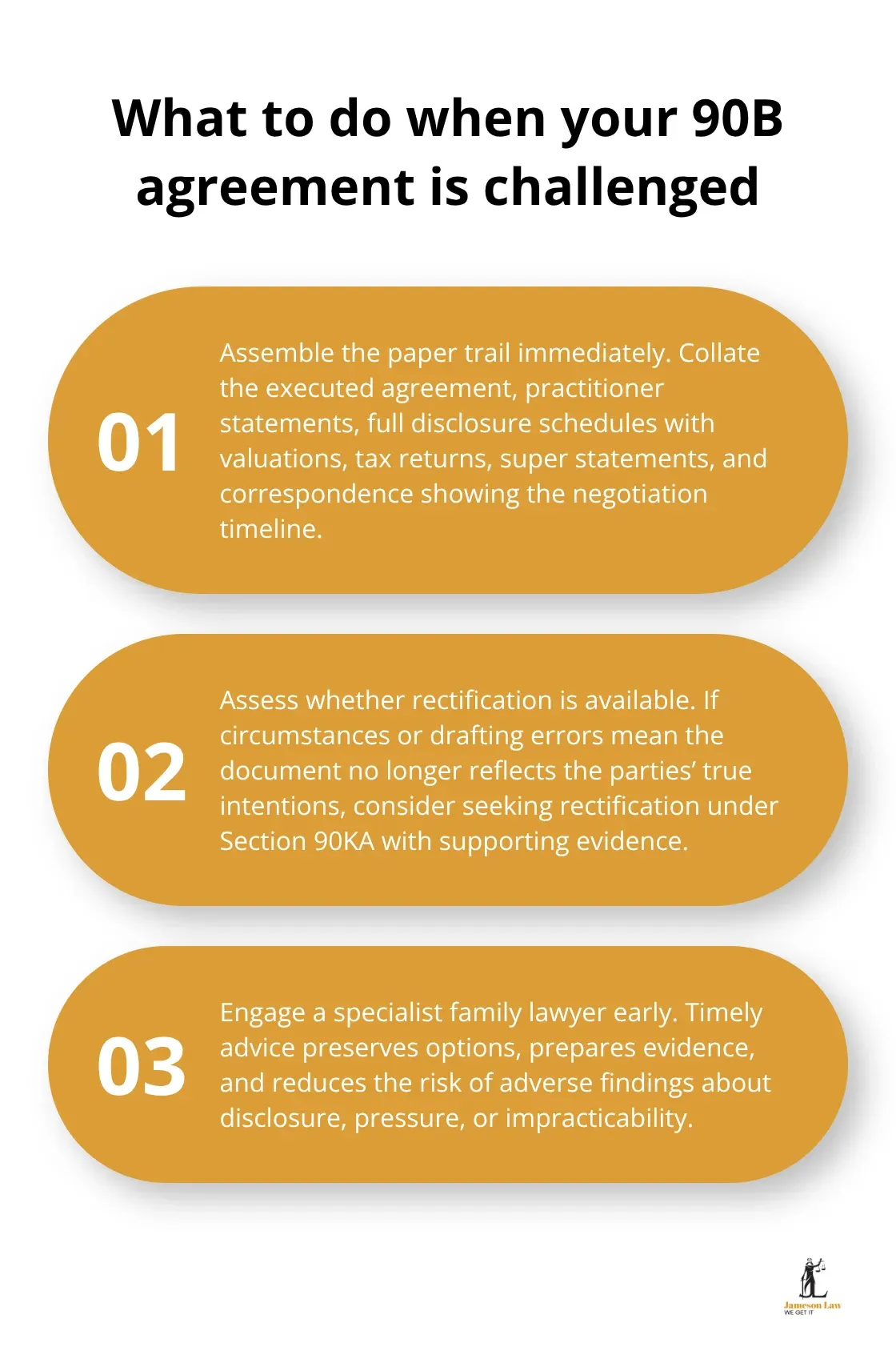

Practical Steps When a Dispute Arises

If you face a challenge to your agreement, gather all documentation immediately: the executed agreement with both signatures, all practitioner statements, complete disclosure schedules with valuations, tax returns and financial statements from the relevant period, superannuation statements, and any correspondence showing the timeline of negotiations. Courts weight contemporaneous documentation heavily when assessing whether disclosure was genuine and whether the parties negotiated at arm’s length. If circumstances have changed materially since signing, you may seek rectification under Section 90KA if the agreement contains mistakes that no longer reflect the parties’ true intentions. In Min v Orton, the court permitted rectification where a common mistake had rendered part of the agreement uncertain or impracticable.

If you need to challenge an agreement or defend one, contact a family law specialist immediately rather than attempting to resolve this alone.

Final Thoughts

Section 90B of the Family Law Act offers real protection when you structure your agreement correctly from the start. The four binding requirements-mutual signatures, independent legal advice from separate lawyers, signed practitioner statements, and delivery of those statements to the other party-form the non-negotiable foundation that courts will examine if anyone challenges your agreement. Full and frank disclosure, professional valuations for significant assets, and timing your agreement months before marriage rather than days before eliminate the most common grounds for challenge.

Litigation over property settlements costs tens of thousands of dollars and consumes years of your life, so a properly drafted Section 90B agreement avoids that entirely. Mistakes at the drafting stage-incomplete disclosure, vague asset descriptions, inadequate independent legal advice, or last-minute presentation-create vulnerabilities that courts will exploit if challenged. These failures are preventable with professional guidance from a family law specialist who understands the technical requirements and can identify weaknesses in draft agreements before you sign.

We at Jameson Law provide expert family law services with over 40 years of combined experience helping clients navigate complex arrangements. Contact us for tailored guidance on your specific circumstances and to ensure your agreement meets every requirement before you marry.