Acting in concert criminal law holds multiple defendants accountable when they work together to commit crimes. This legal principle applies even when each person plays a different role in the offence.

We at Jameson Law see these cases regularly in NSW courts. Understanding how prosecutors prove joint criminal responsibility can make the difference between conviction and acquittal.

What Defines Acting in Concert Under NSW Law

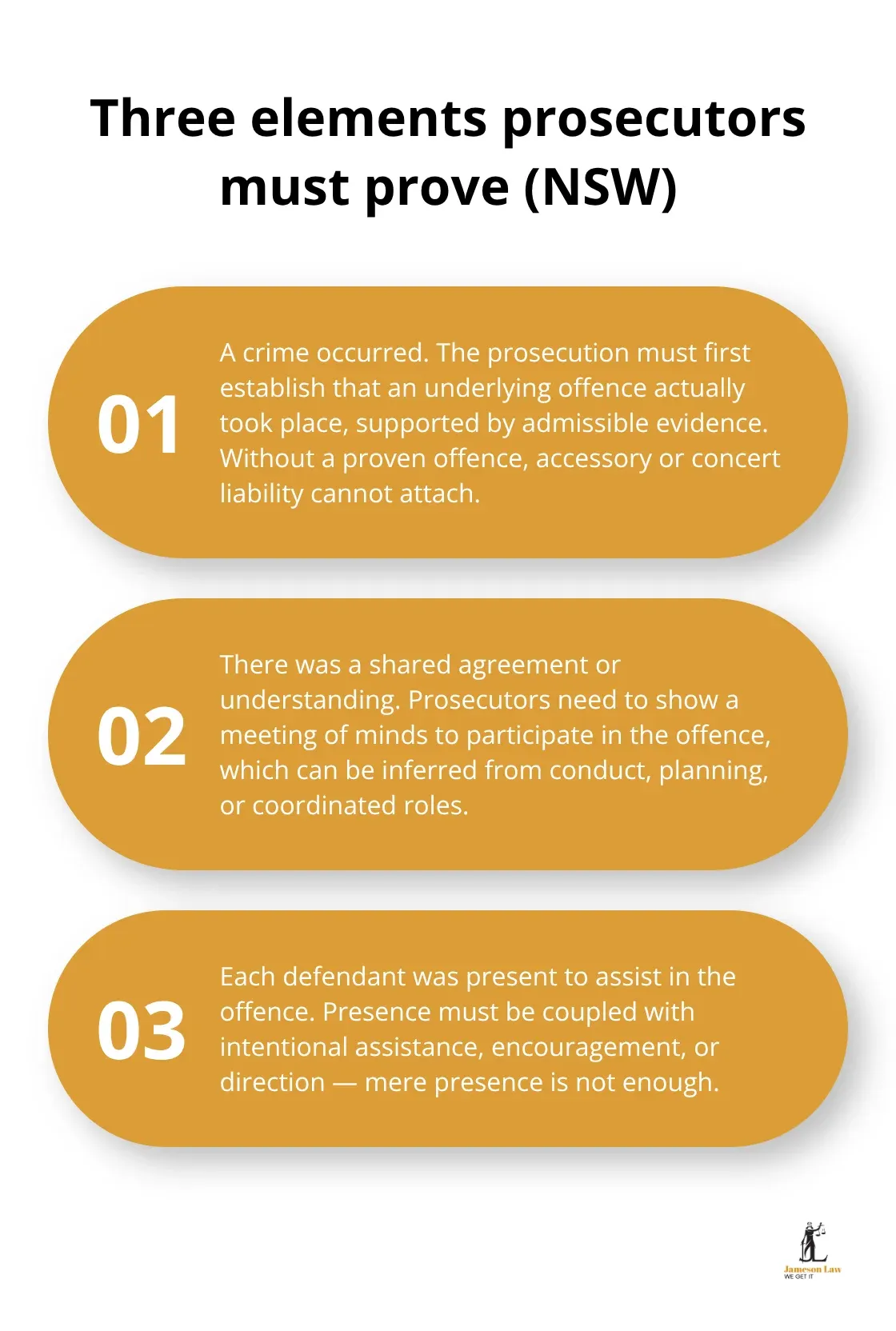

Acting in concert occurs when two or more people participate in a crime through shared understanding or agreement. Prosecutors must prove three essential elements: a crime took place, an agreement existed between participants, and each defendant was present to assist in the offence.

NSW courts apply principles of joint criminal enterprise, which replaced earlier common law principles and establishes that participants face identical penalties to principal offenders.

Legal Requirements for Prosecution

Prosecutors face significant challenges when they prove these charges. They must demonstrate beyond reasonable doubt that defendants shared a common purpose at the time of the offence. Mere presence at the crime scene proves insufficient – courts require evidence of intentional assistance, encouragement, or direction. The O’Dea case established that constructive murder incorporates common law rules of attribution of acts embodied in joint criminal enterprise (this principle applies across Australian jurisdictions). NSW courts consistently rule that passive observation without active participation cannot establish guilt under these provisions.

Key Differences from Joint Criminal Enterprise

Acting in concert differs fundamentally from joint criminal enterprise in scope and application. Joint enterprise typically involves broader criminal activities where participants share responsibility for all foreseeable consequences of their agreement. Acting in concert focuses specifically on the immediate offence where defendants actively participated. The Commonwealth Criminal Code recognises that offenders who act in concert in the commission of an offence are parties to a joint criminal enterprise, while NSW provisions maintain distinct categories. This distinction matters significantly at sentencing, as defendants may face different penalties based on their specific level of participation rather than blanket joint responsibility.

Withdrawal from Criminal Agreement

Defendants can avoid liability if they withdraw from the agreement before the crime occurs. The withdrawal must be communicated clearly to all parties involved and happen in a timely manner (courts assess this based on specific circumstances). A simple change of mind or feelings of regret does not constitute effective withdrawal. The person must take reasonable steps to prevent the offence and issue what courts call a “timely countermand” to other participants. In cases involving drug-related crimes, defendants may also claim duress as a defence if they participated under threat or coercion. These cases demonstrate how complex criminal law becomes when multiple parties face charges for the same offence.

How Do Prosecutors Prove Acting in Concert

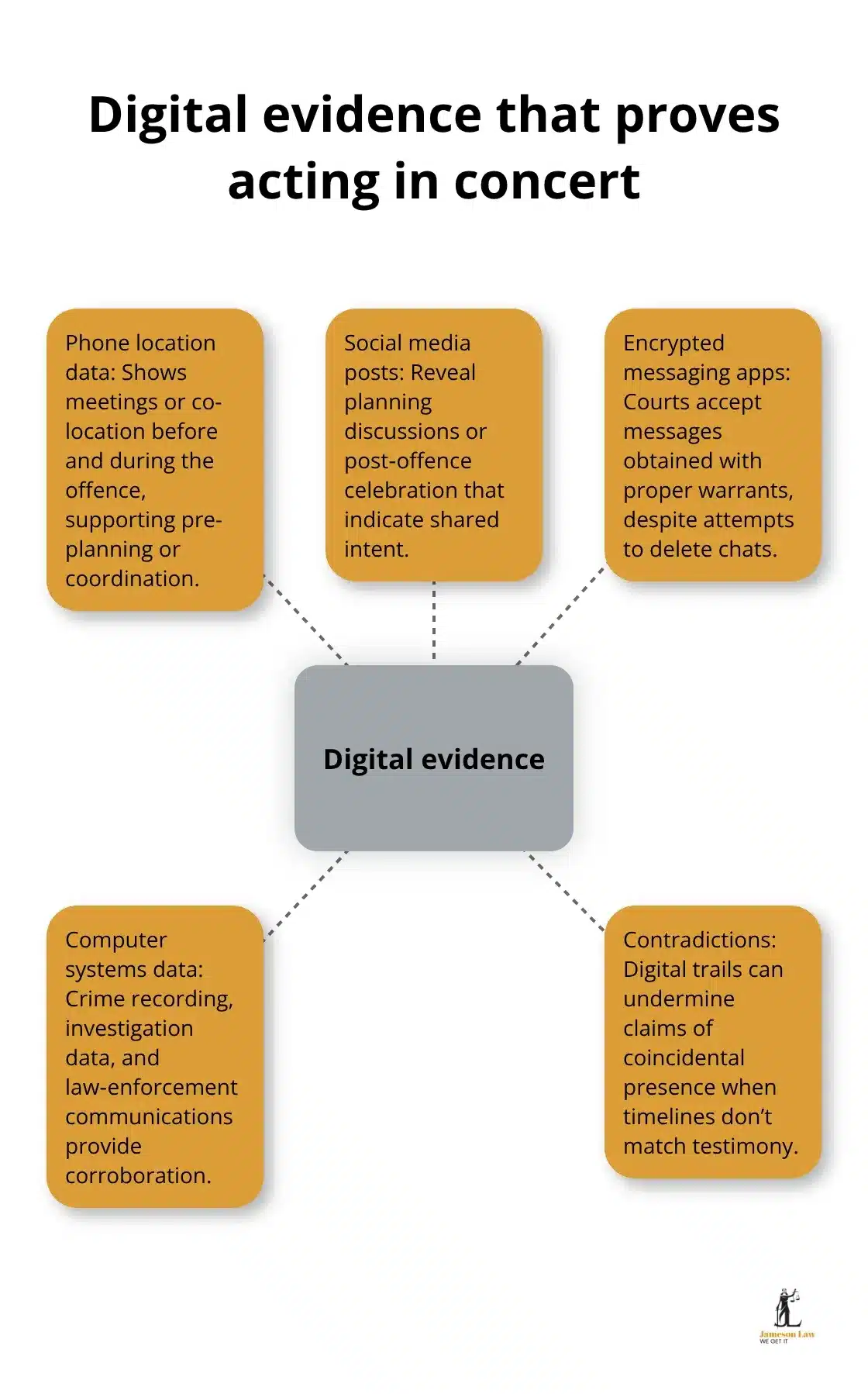

Prosecutors must present specific evidence to establish acting in concert charges in NSW courts. The evidence requirements go far beyond proof of individual participation – courts demand proof of shared understanding between defendants at the time of the offence. Text messages, phone records, and surveillance footage often provide the strongest evidence of pre-planning and coordination. NSW courts examine witness testimony carefully, particularly from co-offenders who agree to testify against former associates. Digital evidence cases present significant challenges for prosecutors due to the sensitive nature of the evidence and vulnerability of research participants involved in criminal investigations.

Intent and Knowledge Requirements

The prosecution must prove defendants possessed specific intent to assist in the criminal activity, not merely awareness that a crime might occur. NSW courts distinguish between reckless presence and intentional participation – defendants who actively encourage violence through words or gestures face conviction, while those who simply fail to leave the scene may avoid liability. Knowledge requirements vary based on the offence type: robbery cases require proof that defendants understood the target and method, while assault cases focus on shared intent to cause harm. Prosecutors face challenges with proof of intent, particularly when defendants claim they attended only to prevent violence or retrieve property.

Evidence of Agreement Without Direct Communication

Courts accept circumstantial evidence to establish agreements between defendants, particularly when direct communication evidence is unavailable. Synchronised movements, coordinated roles during the offence, and similar weapon choices can demonstrate shared planning. NSW prosecutors frequently rely on pattern evidence that shows defendants acted with unusual coordination or timing that suggests prior agreement. The prosecution standard requires proof beyond reasonable doubt, but courts allow juries to infer agreements from conduct that would be highly unlikely without prior planning (expert testimony from criminal behaviour analysts increasingly appears in complex cases where multiple defendants claim coincidental presence at crime scenes).

Digital Evidence and Modern Prosecution Methods

Modern prosecution relies heavily on digital footprints to establish criminal agreements. Phone location data can prove defendants met before crimes occurred, while social media posts often reveal planning discussions or celebration after offences. Computer systems have expanded over decades to include processing of data for crime recording and investigation, along with communication capabilities for law enforcement.

Courts have accepted evidence from encrypted messaging apps when police obtain proper warrants, though defendants often delete conversations before arrest. These technological advances have transformed how prosecutors approach acting in concert cases, making it harder for defendants to claim coincidental involvement when digital evidence contradicts their testimony.

When Does Acting in Concert Apply in Real Cases

Group Assault and Violence Cases

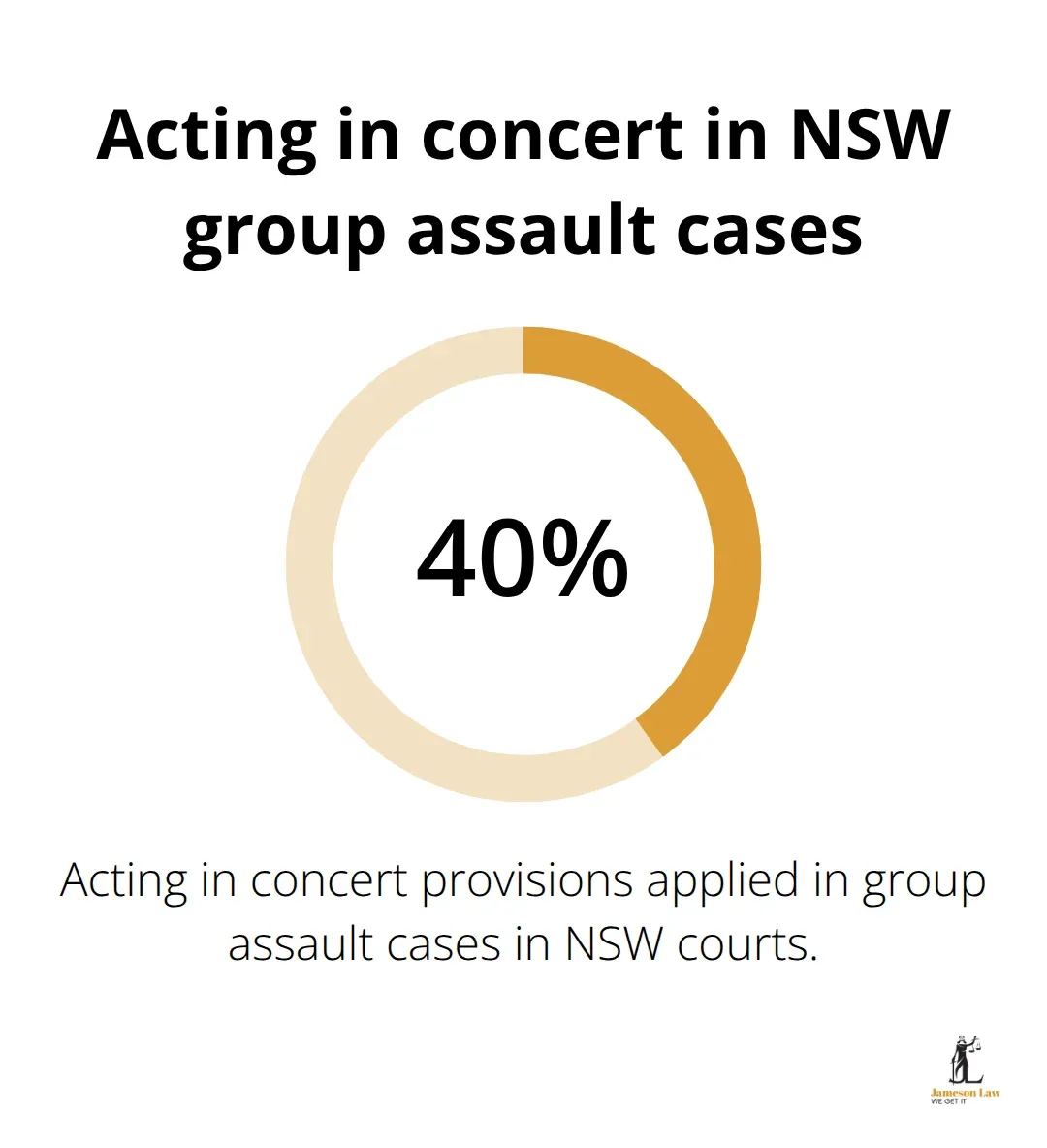

Group assault cases represent the most common application of acting in concert charges in NSW courts. When multiple defendants participate in a fight, prosecutors examine each person’s role to determine shared responsibility. The NSW Bureau of Crime Statistics and Research provides data on criminal sentencing patterns, with acting in concert provisions applied in approximately 40% of these cases.

Courts focus on evidence of encouragement, such as verbal threats, physical placement to block escape routes, or coordinated attack timing. Defendants who claim they only intended to watch often face conviction when evidence shows they positioned themselves strategically or made statements that encouraged violence. Prosecutors prove shared intent through witness testimony and video evidence that demonstrates coordinated behaviour.

Robbery Operations and Coordinated Theft

Robbery cases frequently involve acting in concert charges because these crimes typically require coordination between multiple participants. NSW courts examine role distribution among defendants: lookouts, getaway drivers, and those who directly confront victims all face identical penalties under joint criminal enterprise principles.

The Australian Institute of Criminology examines recorded crime statistics and robbery charges, which makes acting in concert a standard prosecution strategy. Prosecutors focus on pre-planning evidence that includes reconnaissance visits, weapon procurement, and escape route planning. Even defendants who remain in vehicles face conviction when evidence shows they participated in planning meetings or provided transportation with knowledge of the intended crime.

Drug Distribution Networks and Supply Chains

Drug-related criminal activities present complex acting in concert scenarios because participants often operate at different levels of the supply chain. NSW courts hold street-level dealers and suppliers equally responsible when evidence shows coordinated distribution efforts. The Australian Criminal Intelligence Commission produces data on illicit drug activities with endorsement from police commissioners.

Prosecutors examine communication patterns, financial transactions, and territorial arrangements to prove coordinated activities. Defendants who claim they only transported packages or stored drugs temporarily face conviction when evidence shows they understood their role within a larger distribution network. Courts consider compensation patterns and regular participation as strong indicators of intentional involvement (rather than coincidental presence at crime scenes).

Final Thoughts

Acting in concert criminal law creates serious legal consequences for anyone involved in group criminal activities, regardless of their specific role. NSW courts hold all participants equally responsible when prosecutors prove shared understanding and intentional assistance in committing offences. The prosecution must establish three key elements: a crime occurred, defendants agreed to participate, and each person was present to assist.

Evidence requirements go beyond mere presence at crime scenes – courts demand proof of active encouragement, coordination, or assistance. Digital evidence, witness testimony, and circumstantial proof of planning often determine case outcomes. Defendants face identical penalties to principal offenders under joint criminal enterprise principles (withdrawal from criminal agreements remains possible but requires clear communication to all parties before the offence occurs).

Professional legal representation becomes essential when facing these charges. The complexity of proving shared intent and the severe penalties involved make expert criminal defence necessary for protecting your rights and achieving the best possible outcome. We at Jameson Law provide experienced criminal defence representation across NSW for clients facing group criminal charges.