Australia’s migration story spans over 65,000 years, from Indigenous settlement through European colonisation to modern skilled migration programmes. The waves of migration to Australia have fundamentally shaped the nation’s economy, culture, and identity.

At Jameson Law, we recognise that understanding this history is essential for anyone navigating Australia’s current immigration landscape. This overview traces how successive migration movements have transformed Australia into one of the world’s most multicultural societies.

How Indigenous Australians and European Colonisers Shaped Australia’s First Migration Waves?

Indigenous Settlement: 65,000 Years of Continuous Culture

Australia’s migration story did not begin with Europeans. Indigenous Australians arrived at least 65,000 years ago and established the world’s oldest continuous culture. Archaeological evidence from sites like Madjedbebe reveals sophisticated settlement patterns tied to land management.

Terra Nullius and the Misrepresentation of Indigenous Australia

Captain James Cook’s 1770 voyage led to the assertion of terra nullius (“land belonging to no one”). This legal fiction ignored thriving Indigenous nations and shaped colonial policy for nearly two centuries, leading to dispossession.

Convict Transportation: Forced Migration and Colonial Settlement

The first European wave arrived as convicts in 1788. Britain and Ireland transported over 160,000 convicts to establish penal colonies. This forced migration created Australia’s initial European population, fundamentally different from voluntary settlers.

Gold Rush and Industrial Transformation

The 1850s Gold Rush Reshapes Migration Patterns

The 1850s gold rush triggered massive voluntary migration. Victoria’s population exploded from 77,000 to over 540,000 in a decade. Chinese miners formed a substantial portion of this wave, facing discriminatory laws like the Immigration Restriction Act 1855 in Victoria.

Post-War Migration and the Populate or Perish Campaign

Post-World War II migration was driven by the “Populate or Perish” campaign. Australia launched assisted passage schemes for British migrants (the “Ten Pound Poms”) and welcomed over 170,000 Displaced Persons from Europe. This shifted the nation’s demographic from exclusively British to broadly European.

Contemporary Migration and Demographic Shifts

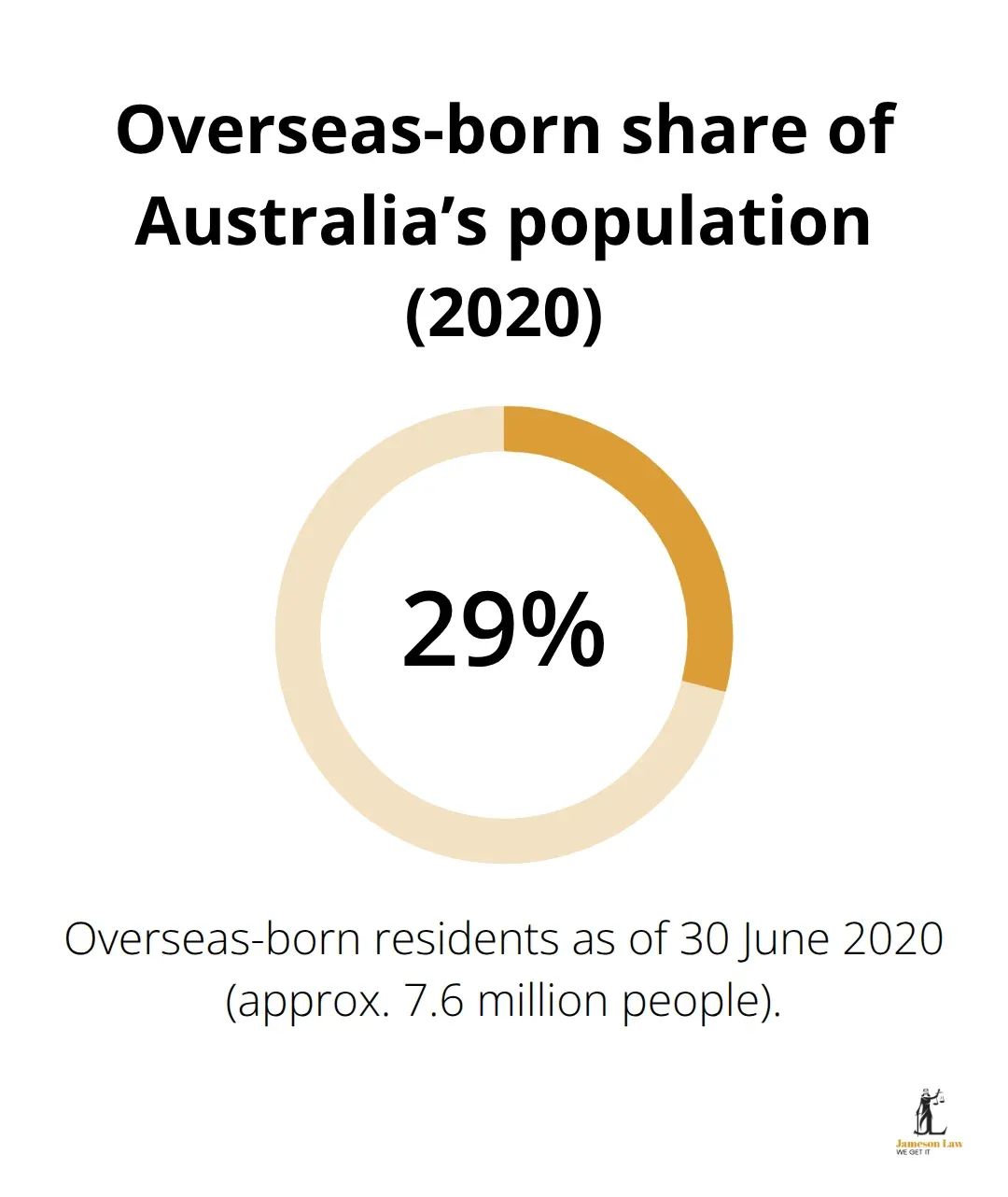

Modern data from the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) shows that as of 2024, approximately 31.5% of Australia’s population was born overseas. England remains the largest source country, followed closely by India and China.

How Australia’s Migration System Works Today?

From Racial Exclusion to Skills-Based Selection

Australia’s migration system transformed with the end of the White Australia policy in 1973. Today, the system prioritises skills. The Skilled Migration Program targets workers in shortage occupations, driving economic growth.

Migration’s Impact on Employment and Innovation

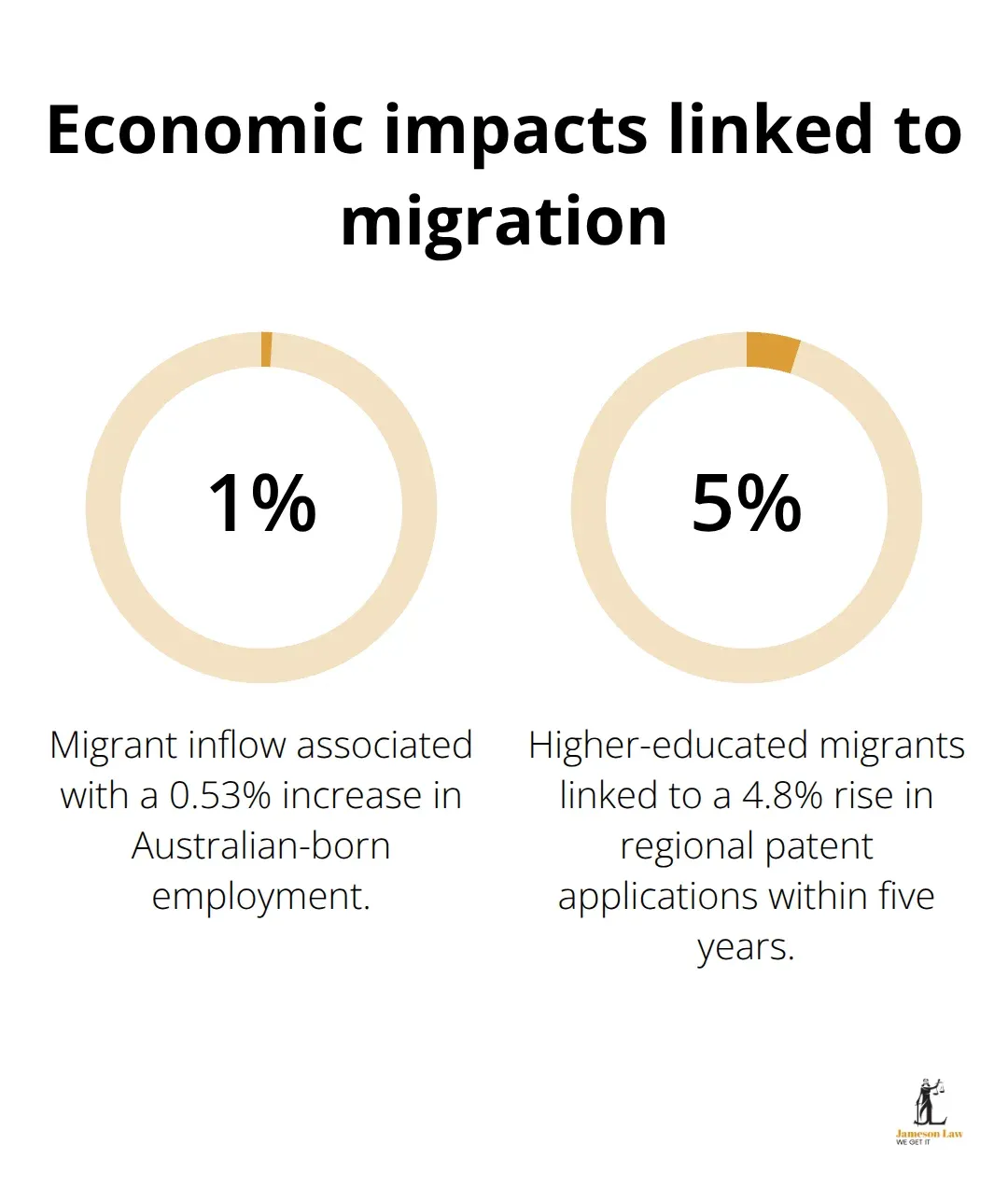

OECD research demonstrates that a 1% increase in migrant inflow is associated with a 0.53% increase in Australian-born employment. Furthermore, higher-educated migrants boost regional innovation, with a 1% increase in their employment share leading to a 4.8% rise in patent applications.

Final Thoughts

Australia’s waves of migration transformed the nation from a penal colony into a multicultural powerhouse. From Indigenous heritage to post-war reconstruction, every wave has added a layer to our national identity.

The policy framework has evolved from exclusion to skills-based selection. If you are considering family sponsorship or skilled migration, contact Jameson Law. Our team provides tailored guidance grounded in Australia’s complex immigration history and current laws.