Legal causation in criminal law is a complex yet fundamental concept that underpins many criminal cases.

At Jameson Law, we understand the importance of establishing a clear link between a defendant’s actions and the resulting harm.

This blog post breaks down the key elements of legal causation, explains the main tests courts use to determine it, and gives practical examples to show how it applies in real NSW matters.

What Is Legal Causation in Criminal Law?

Legal causation in criminal law describes the cause-and-effect relationship between the accused’s conduct and the harm suffered by the alleged victim. It is central to serious offences such as murder or manslaughter under the Crimes Act 1900 (NSW) s 18.

Components of Legal Causation

Legal causation has two main components:

- Factual causation — Was the conduct a necessary condition of the harm? See our short primer on causation concepts in remedies and proofs.

- Legal causation — Is it fair and reasonable to hold the accused responsible, given policy and foreseeability considerations?

The Importance of Causation in Criminal Cases

The prosecution must prove causation beyond reasonable doubt for a conviction. Without causation, criminal liability will not attach even if conduct appears morally blameworthy. In Royall v The Queen (1991) 172 CLR 378, the High Court confirmed that responsibility is made out where the accused’s acts are a “substantial or significant cause” of death — not necessarily the sole cause.

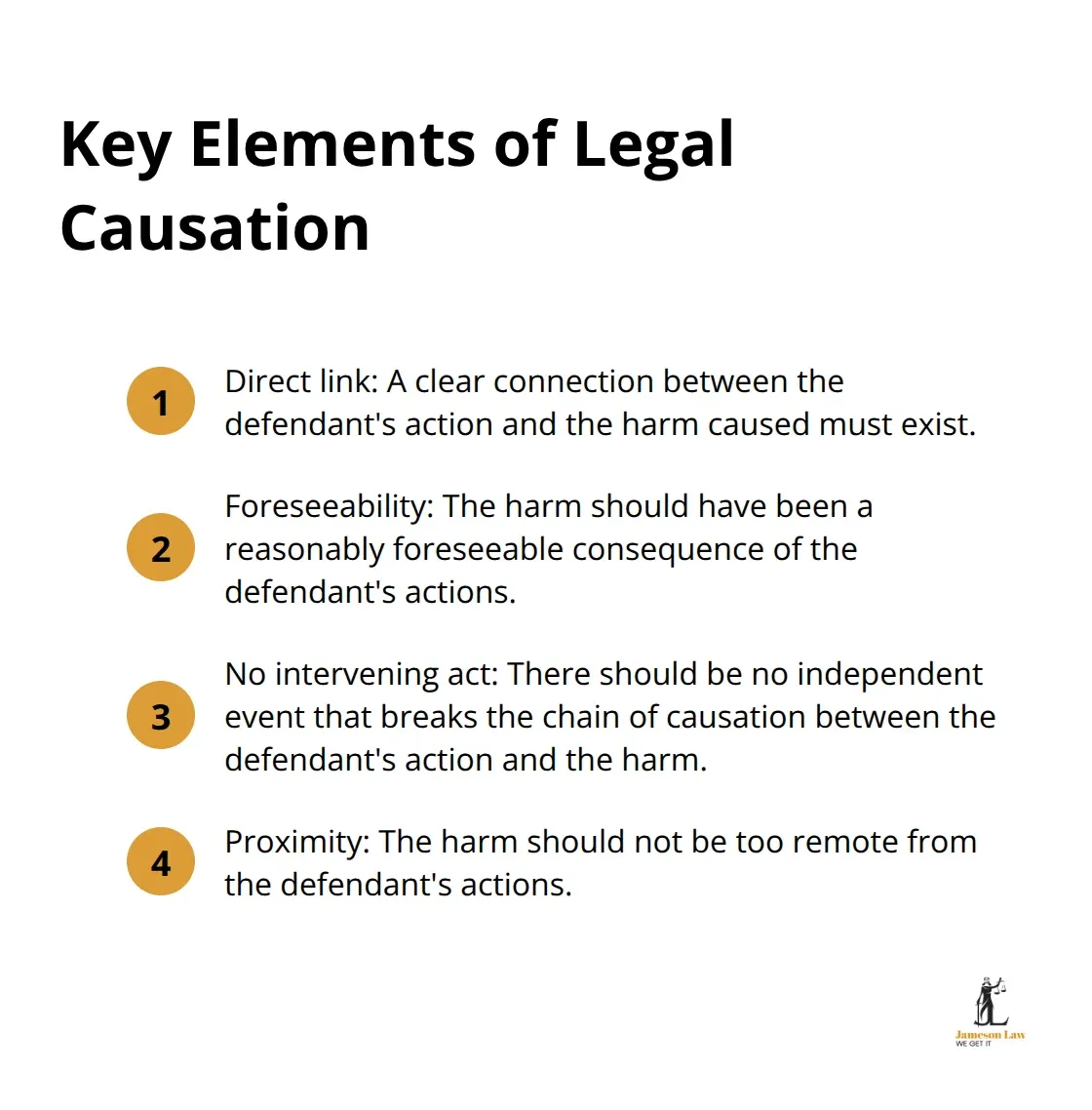

Key Elements of Legal Causation

Courts commonly look for:

- A direct or sufficiently close link between conduct and harm

- Reasonable foreseeability of the type of harm

- No novus actus interveniens (intervening act) breaking the chain

- Proximity in time and circumstance

Practical Application

In practice, causation can be contested. For example, medical questions may require expert evidence on whether conduct made a material contribution to death or injury. In drug-related deaths, prosecutors often argue the accused’s supply was a substantial cause despite other factors. Our trial representation team regularly addresses causation disputes and how an intervening act may break the chain.

To understand the broader NSW criminal process, see our guide to criminal law in NSW and what happens in criminal matters.

How Courts Determine Legal Causation

Australian courts use several well-known tests when assessing causation. These inform how responsibility is assigned and often decide outcomes.

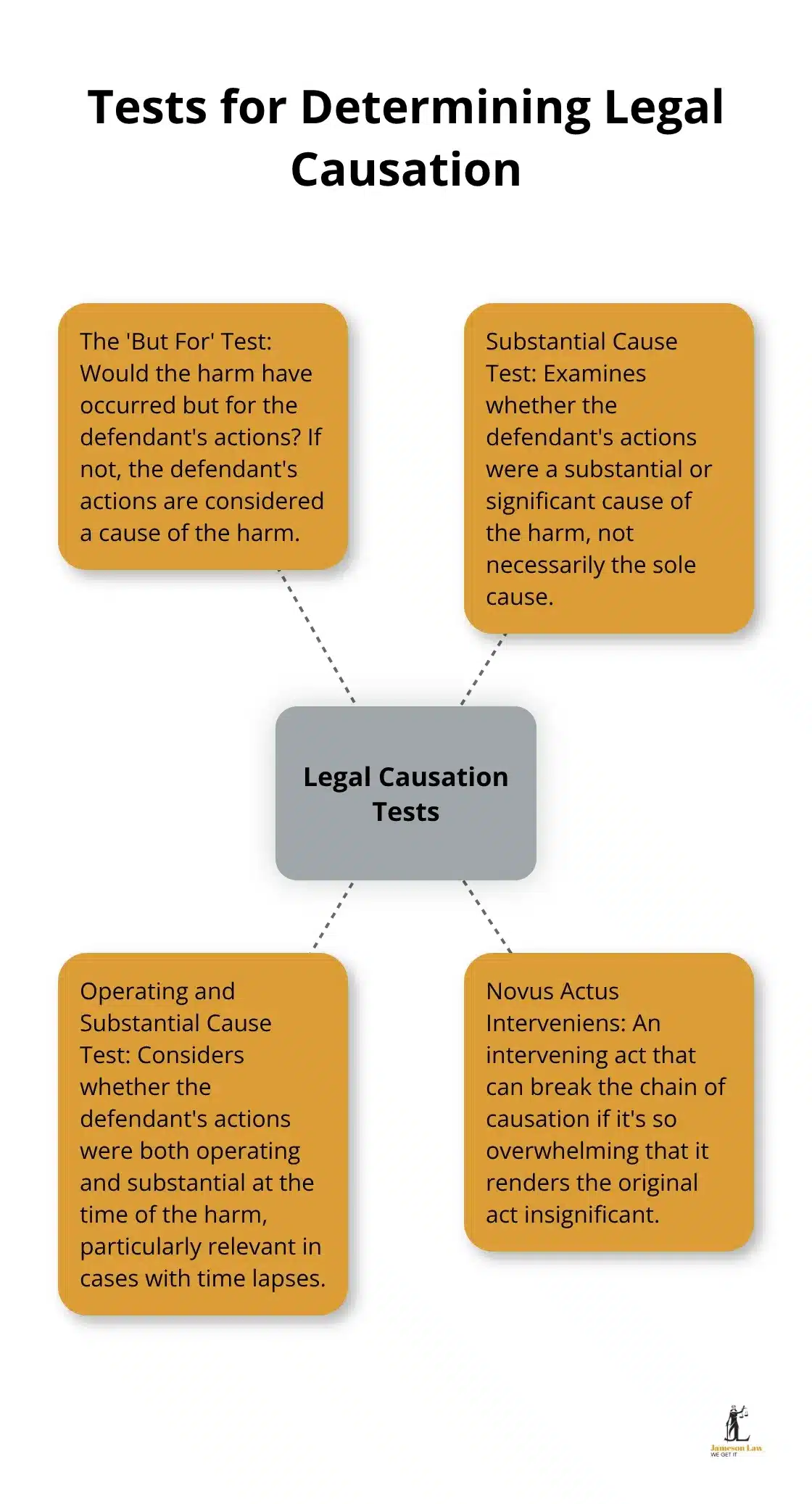

The ‘But For’ Test

The first inquiry asks: would the harm have occurred but for the accused’s act or omission? If not, factual causation is indicated. See our overview of causation basics in It’s all about remedies. For classic discussion, compare UK authority R v Smith (1959).

The Substantial Cause Test

Courts then consider whether the conduct was a substantial or significant cause of the result. In Australia, Royall v The Queen confirms that multiple causes can operate together — it need not be the only cause.

Operating and Substantial Cause

Liability can still attach where the accused’s conduct remains an operating and substantial cause at the time of death or injury, even after some lapse of time. See discussion of R v Hallett (1969) SASR 141.

Novus Actus Interveniens (Intervening Act)

An independent, overwhelming event can break the chain of causation. The bar is high. Under the “thin-skull rule”, the accused must take the victim as found. See R v Blaue (1975) and our primer on the chain of causation.

For prosecution policy on responsibility and proof, review the NSW DPP’s Prosecution Guidelines. If you are facing charges, our Sydney criminal defence team can advise on the best strategy.

Real-World Examples of Legal Causation in Criminal Law

These examples show how principles work in practice.

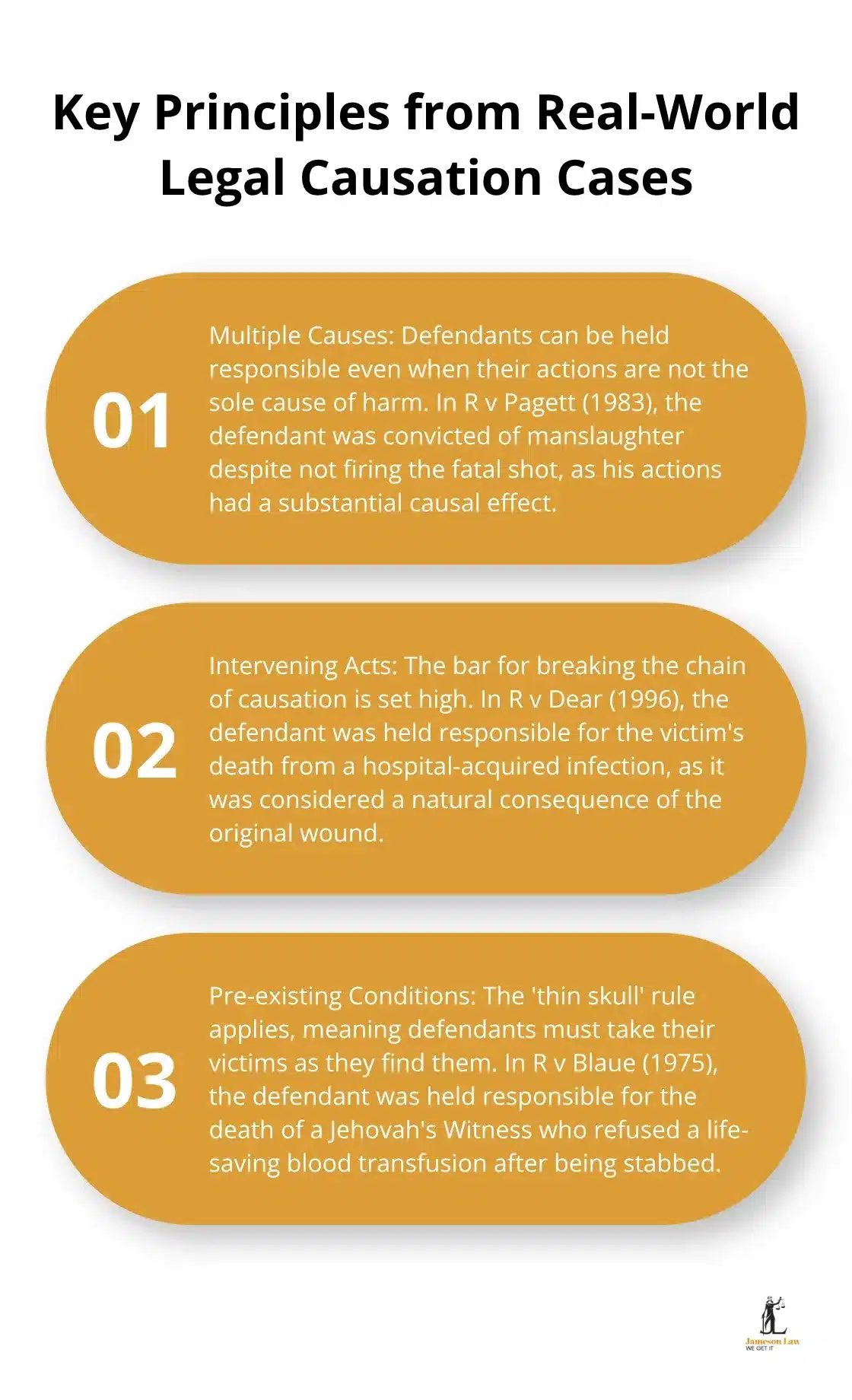

Multiple Causes

Where several events contribute to the result, liability can still follow if the accused’s act is substantial. See R v Pagett (1983) for a classic illustration.

Intervening Acts

A later event usually will not break the chain if it is a natural consequence of the original injury. Compare English authority often discussed in texts; Australian courts adopt a similarly cautious approach to novus actus. Our criminal lawyers test whether an alleged intervening act truly severs responsibility.

Pre-existing Conditions

Under the thin-skull rule, the accused is responsible for the victim’s actual condition. See Blaue.

Omissions

Failures to act can ground liability where a duty arises. See R v Miller (1983). In NSW proceedings, duties and omissions are assessed against local statutory and common-law principles — get advice early on your available defences.

For procedure and court stages, see our overview of NSW criminal court procedures.

Final Thoughts

Legal causation sits at the heart of criminal responsibility in NSW. Tests such as the but for inquiry, substantial cause, operating and substantial cause, and intervening acts guide courts in deciding whether liability should attach.

If you are being investigated or charged, prompt advice can be decisive. Speak with our Sydney criminal defence team for clear guidance on evidence, expert input and strategy. Call (02) 8806 0866 or contact us for a confidential consultation.